Uncategorized

Check out 25YearsLater

I am now a regular contributor to the 25 Years Later website, where you can find the latest in Twin Peaks fun, with podcast reviews, theories and analysis, debates and other fun articles from fan contributors!

STAR WARS: The Creation of a Modern Myth: Cultural Influence, Fan Response and the Impact of Literary Archetypes on Saga Perception

By E.G. Mykkels

“It’s hard to remember a time before Star Wars” states Robert Clotworthy in his narration for the 2004 Documentary Empire of Dreams. Indeed, personally, I find it almost impossible. I’d like each and every one of you reading this to take a moment. Recall the first time you saw Star Wars–how old you were, which film it was, the circumstances it was under. Recall how you felt, who you were with, what you were eating, and, if you can, where you were. Immerse yourself in the memory of how that felt.

Star Wars, for me, was a rite of passage. I was seven, almost eight. My Dad and my brother argued for an hour over where to start. My dad, ever the king of his castle, wanted to watch podracing, so we started with The Phantom Menace, despite my brother’s insistence that they start me off with A New Hope. Over the next two days, I watched all five Star Wars films. Three years later, Revenge of the Sith premiered. I saw it in the theatre, with my dad, my brother and my brother’s best friend. It was an experience I’ll never forget.

In the span of those three years I read every Star Wars novel and comic trade paperback my library had. I watched The Ewok Adventure, I learned the music for piano. I watched the first Clone Wars show from 2003 religiously. I rewatched the five films on a loop, driving my family insane. I collected almost all the soundtracks. I would drive with my Dad to stores over an hour away to get Lego kits which I then built and displayed. I played Empire at War with my brother. I went to Disney World and did the MGM Backlot tour(back when it was still there) and got a picture with the actual suit of Darth Vader from ANH when I was nine. I own back issues of Star Wars Insider magazine. I was Anakin Skywalker for Halloween in 2005. I have, hanging, framed, one of a limited run of the Episode III posters that hung at the Chicago premiere. I lived and breathed Star Wars like it was my very lifeblood.

My brother, as mentioned, argued with my Dad about which movie to show me first. A bit about my brother. He’s 14 years older than me. Born in 1980, he grew up around our cousins, almost a decade older than him, who saw the Original Trilogy in theatres (one even named his son Luke). He collected Lego kits, and played Empire at War, but he did not live and breathe Star Wars.

My dad now claims he only ever enjoyed Star Wars because of us kids, and can’t watch it without finding something to complain about.

So obviously, my family and I are of very different opinions. But there are two things, in recent times, all of us have agreed upon.

The Force Awakens is a terrible movie. Rogue One isn’t.

When I saw TFA the day of its premiere I wanted to walk out of the theater, but I had to drive someone home. I was sick to my stomach. I hated it so vehemently that I wanted my money back, and I hadn’t even paid for my own ticket. My dad, when he got home, told us that he didn’t like Star Wars anymore, turned to me, and said I could have all of the movies (that’s five VHS tapes and one DVD), that he didn’t want them anymore, and didn’t care to watch them. My brother said it was a pathetic rip off of A New Hope.

So you have my brother, the OT fan, my Dad, the ambivalent “general audience proxy” and me, the Saga fan, who loves the OT and PT equally, and we all found common ground in TFA. Small mercies. But why am I telling you all of this?

Star Wars is a cultural movement. A phenomenon like Lord of the Rings, and one that’s been ripped off and spun off and which has inspired so many things, but which can never, never be precisely replicated . It revolutionized the film industry, and changed Hollywood and the science fiction genre forever. None of these things are in dispute. There have been documentaries made about how Star Wars affected the world, from the popular culture to even the political climate of the day. Years ago, a teacher at my high school used Star Wars to teach different types of political systems. The upcoming Legends of Tomorrow episode reportedly focuses on how critical Star Wars is to the timeline, that people whose lives were impacted by Star Wars wouldn’t be what they became without it: scientists, authors, professors, etc. I myself have been irrevocably formed by my experiences with Star Wars. I might not be a high school teacher today, if things had been different.

Star Wars has affected people, regardless of when they saw it, how deeply they delved into it, which version of the films they saw, or even what order they saw them in. Most people are like my dad. The analogue of the “general audience”, he enjoyed the movies on a base level. He liked all of them at least a little, took them for what they were. He could care less about tie-in comics, novels, games, etc. The only Star Wars he knows is the movies.

My brother is like most ‘more involved’ fans. He collects some memorabilia (the collector’s edition display model Legos) and has played some video games. He prefers the OT but will watch the PT. That’s pretty much the end of it.

I don’t fit most of the clear cut Star Wars fan models, purely because I enjoy the Prequel trilogy in addition to all of the other things that make me a ‘run of the mill’ Star Wars fanatic.

Way back in 2000, George Lucas came forward with a model to keep things in his sandbox organized. Called the Holocron continuity database (run by Leland Chee, for those interested). It organized things into levels of continuity as follows: G-canon (the six films, any unpublished notes, deleted scenes etc and if George decreed it, regardless of where it came from, it was canon. This is gospel. If anything conflicted, G-canon was the whole and ultimate truth), T-canon (anything on any television show), C-canon (continuity canon, consisting of all recent works (and many older works) released under the name of Star Wars: books, comics, games, cartoons, non-theatrical films, etc), S-canon (i.e. secondary canon, the materials are available to be used or ignored as needed by current authors. This includes mostly older works, such as much of the Marvel Star Wars comics, that predate a consistent effort to maintain continuity), N-canon (non-canon, i.e. What-if stories) and D-canon (Detours Canon).

This meant that all those exciting books and tv shows and comics could be written and made without accidentally conflicting with something in the six film saga. It meant that George Lucas could allow others to have fun in his sandbox without worrying about every little detail being presented correctly. It meant that if things weren’t quite right, no one cared.

There’s a lot of discourse (for old folks, read as fandom wank) these days over how much right to their own works an author has. Fanfiction, of which I’ve been an active participant since 2008, is a hot button issue. Authors like George R.R. Martin and Diana Gabaldon, as well as Ayn Rand are infamous for their refusal to allow people to write fanworks about their characters.

The rebuttal to that, of course, is that fanworks are just that: fan works. They are not canon, they are head canon. People have certain views and beliefs about pieces of media–Star Wars included– that they develop regardless of the author or creators perception. That’s only natural. It is when fans decide that the creator of the media in question owes something to thems, that problems arise.

There is, perhaps, something understandable and justified in this. For instance, when writing is particularly poor in quality, or retcons are being made haphazardly without being addressed, or when mistakes within the material are frequent and attempts to cover them up are thinly veiled PR control, then the fans have the right to take issue. While the owners of the intellectual property certainly have the right to misuse and abuse their own material, that doesn’t make it good for them. Fans are likely to take issue with that, and feel like they are owed better for supporting the media in question.

This is not the case, however, with Star Wars. In the documentary Empire of Dreams (2004) Lucas stated “[…] I did have a very strong feeling about being able to be in control of my work and not having people tamper with it,” This was a feeling that resulted, largely in response to the control Hollywood exerted over all mainstream films at the time, and, truth be told, still does, perhaps to an even greater degree. Before embarking on his Star Wars journey, Lucas joined the independent film company American Zoetrope, a group founded by his good friend and fellow student Francis Ford Coppola, in effort to escape Hollywood’s controlling nature.

Each bit of material that Lucas added to the Star Wars universe was heavily deliberated over, especially at the onset. Many ideas remain only as asides, the Journal of the Whills, for instance, and Luke and Anakin’s origin as Starkiller rather than Skywalker. Lucas’ heavy personal investment in the maintenance and fluidity of his Saga was phenomenal. Every retcon he made, was made with a purpose and fitted as seamlessly as possible to the preexisting canon before he moved on. Yet, fans in recent years, going back almost to Y2K, seem to have felt like Lucas owed them something more.

When The Phantom Menace was released in 1999, the initial response, dating almost a month post the film’s release, was extremely positive. Mull that over once. People loved TPM. They came out of the theatres raving about it. There’s footage. You can look it up. People saw it twice, three times. It wasn’t the revolutionary phenomenon ANH was at the time of its release, but it was the film many had been waiting for, for years. What changed, then, to make it so that most of you recall (that is, if you were alive or aware of Star Wars in 1999,which some of you might not be) the immediate response to TPM as being overwhelmingly negative?

In his article hosted at Ferdy on Films, Roderick Heath recounts the history of the Prequel Trilogy:

“Facing a new trilogy with much darker and less commercial subject matter than his first series, Lucas at first courted a new generation of young viewers as fans, but he left many feeling he conceded to those young folk excessively. The people who already loved Star Wars certainly weren’t kids anymore: they were 20- and 30-somethings who wanted, whether they knew it or not, two completely divergent yet equally necessary sensations: the feeling of being thrust back to childhood even whilst simultaneously acknowledging their evolution. The Matrix, released a few months before The Phantom Menace, became the film the latter singularly refused to be: a superman fantasy dressed up in pseudo-grit and cyberpunk quotes that fitted the mood of the time. The Phantom Menace was a huge hit, but soon became a byword for the cultural equivalent of a fumbled touchdown. That said, I was and still am bewildered by the level of invective the prequel trilogy receives. In some ways, I even prefer those films today. I don’t say this just for the sake of contrariness. Some criticism levelled at the trilogy is legitimate and feelings of dashed expectations are honest enough for many. But I also feel this cult of disdain was an exemplification of something notably obnoxious about the dawning age of the internet, a deeply spoiled capacity to judge with distinction or consider with a sense of history that refers outside of the bubble of fandom, or the opposite, charmless snootiness turned on popular cinema.”

What Heath alleges here is that the age of the main fanbase, the rise of the internet, and the release of Episode I created an atmosphere that was too turbulent for the burgeoning prequel trilogy. After the initially favorable reception, some of the dissatisfied fans who comprised just the right (or wrong, depending on your point of view) combination of factors and emotions, took to the internet, and, as a result, actually managed to peddle their views to a greater public and convince them of their viability. If TPM had been released a little sooner, or the internet had developed a little later, this very likely would not have occurred, and the general outlook on the prequel trilogy today might be vastly different. The internet provided this small group of fans a platform through which to voice their views within the infant fandom groups online and influence far more people in the general audience than they would have been able to prior to this time period.

From this point forward, opinions become split. My brother was one such person affected by this. He had initially been very fond of TPM but altered his views some time later, after reading some scathing reviews on the internet. This influence from members of his and other’s peer groups literally altered the outlook on Episode I and prematurely damned the following films by proxy. (As an aside, the definition of peer pressure, a generally negative thing, is as follows: “the influence from members of one’s peer group”.)

Now, like Heath, I agree that there are issues with the PT, whether it be in dialogue or plot. However, there are also issues with the OT, as there are with anything. Storytelling problems are inherent to stories. Nothing is perfect. Parts of each of the six films that comprise the Saga are cheesy, campy, have plot holes etc. This is a byproduct of writing. But Star Wars catches more flack for this simply by virtue of the fact that it is Star Wars. Here again, we have the issue of fan entitlement. Star Wars is held to the highest of all standards. A god, called Nostalgia.

From the release of Episode I all the way up to the very moment I write this and beyond, fans have complained and will likely always complain about the prequels simply due to the fact that they had already come up with their own ideas in the meantime between the release of the OT and the PT and did not see them fulfilled. In other words, they got Jossed, and weren’t happy about it. If the PT had been released in the ‘80’s, shortly after Return of the Jedi, nothing would be different on that front. People, by nature of being people, inherently create their own ‘headcanons’ about backstories, theorize about future plots, get excited about the ideas they’ve come up with, and then, when it turns out that isn’t so, some have a hard time accepting it. I’m no different. It happens. It’s the nature of the beast. But the length of time made this worse because nostalgia became another inevitable factor.

No summer is as good as the summer of ’98, no school year was better than ’65. No Star Wars movie is as good as A New Hope, or Empire Strikes Back. Nostalgia makes imperfect things appear flawless (as a good friend once said, nostalgia without substance is just a hipster wankfest). ANH is one of the most campy, fun-loving, childish stories I’ve ever heard of, and is considered a nostalgic classic (though it is enjoyed on far more merit that nostalgia alone).TPM, on the other hand, is constantly harangued for being campy, fun-loving, and childish. Attack of the Clones is frequently maligned for being ‘too much like a romance novel’. Another common complaint is that the PT was too focused on politics and serious matters, unlike the OT, which just so happened to be focused on the repercussions of the serious political matters without which there would be no OT story. Even the criticisms of the PT contradict one another, partially because so many of these complaints have no concrete rational basis. Whatever portion conflicts with a personal nostalgic recollection is called into question on an individual basis. Yet, for all the nostalgia and pedestal placing of the OT, there are others who criticize ANH, and tout ESB as being the pinnacle of art, and those who uphold ANH and ESB, claiming Return of the Jedi as being campy. This is an interesting thought. Why do some OT fans come down so hard on ANH in particular, especially in the current day and age? One simple fact. This is a by-product of the PT hate, which found only one universal point to criticize as the ‘source’ of their unhappiness: the creator of Star Wars himself, George Lucas, the sole writer of A New Hope.

After it became popular to dislike the prequels, it also became popular to dislike George Lucas as a result. His writing wasn’t good. He came up with stupid characters. He was too focused on merchandising (I’m looking at you, Disney stans). The actors sucked. Many of these things are, of course, a matter of opinion. In short, those who are generally discontented believe that George Lucas ruined his own work. Many create fanworks to cope with this, a perfectly valid and commendable pursuit, with some creating alternate universes just as rich and impactful as the original source material, the format allowing them to delve more deeply into particular aspects, owing to fact that fanwork is a platform of virtually boundless freedom to do whatever they please. There is nothing wrong with the creation of fanworks. However, some readers of these works go so far as to claim them as their ‘new canon’ in light of their discontent, completely devaluing the things from the source material that they dislike, no matter what they might be, or how important and relevant to the narrative, picking and choosing from canon work to suit their desires. These fans believe that they are owed, or entitled, to the story they want. A story they believe they deserve. The problem is that not one of these fans knows what that story is, or has the same story in mind. All they know is that the one George Lucas wrote isn’t it. It wasn’t what nostalgia told them it should be. It wasn’t the easy to swallow story they expected, or the less than serious space adventure they desired.

It’s easy in my experience, to know what you don’t like, and far more difficult to know what you do. It’s no different with Star Wars. Fan-pandering is a controversial point. In one fandom, the feeling might be that if the writers aren’t pandering, then the show is terrible, in another, the moment pandering occurs, the fans may feel that writing is somehow lessened or rendered invalid. Feelings on this vary from fandom to fandom. There is no consensus, and without a consensus within fandom on what should be, then there can be no legitimate claim from the fans as to what they are owed. Discontent with well-comprised and orchestrated material (occasionally-lacking dialogue or mildly annoying characters aside) does not equate to discontent with poorly written, or poorly executed material. Let me reiterate, the Prequels are not without their flaws, but they are hardly poorly written or executed. In fact, the story they tell is perhaps more complex than most, on a base level. The political intrigue so prevalent in the films is not for everyone, admittedly, but without it, we cannot hope to grasp how the situation the galaxy finds itself in at the beginning of ANH came to be. Without this element, the story that George Lucas tells the viewer any time they sit down to watch, is lost.

While the fans may have been unhappy at Lucas’ refusal to pander to them, he did not allow it to change the vision that he’d spent so long crafting. Rather than bend to the demands of an unreasonable, nostalgia blinded fanbase, Lucas remained true to the integrity of his original story. Whether or not you liked the prequels, his stalwart nature should be admired; most would not be so resilient. Ironically enough, those people who are so committed to the idea of fanservice, seem also to be those people who are unwilling to entertain ideas about the story other than their own, or a chosen few derived from other people. As a writer myself, I can’t see bending to the pressure of the crowd, though their fervent demands might be intimidating. Like Lucas, I imagine. He wasn’t writing for the fans, or even, at that point, for himself. He was writing for the story. Writing the beginning it was owed. Writing the only story that could ever have led to the events of A New Hope and beyond. The story that integrity demanded he tell, everyone else be damned.

From the beginning, Star Wars was conceptualized not as a science fiction film, but as a mythical epic, consistent with those of poetic eddas, from Beowulf to the Iliad and the Odyssey. In Empire of Dreams, these are cited as influences, as well as the Legend of King Arthur, and other assorted Arthuriana, determining that they comprised the pool from which Star Wars drew it’s mythic archetypes. “With his galactic fairytale,” Clotworthy states, “Lucas hoped to reinvent a classic genre. Among his influences, were the writings of scholar and educator Joseph Campbell, in which he explored the origins of myth and world religions.”

“What Joseph Campbell was interested in, was to see the connections between myths, the myths of different cultures, to try to find out what were the threads that tied all these very disparate cultures together,”

Professor and Cultural Historian Leo Braudy, University of Southern California

Lucas, too, was interested in this, in particular when creating Star Wars. Lucas actually asked Campbell to supervise his work on Star Wars, to be sure it fit with what he was trying to convey. Campbell, in turn, described Lucas as his best student. This is truly the crux of the matter. What Lucas was attempting to accomplish was the writing a modern myth, following conventional, thousand year old methods, all the while having it be relevant, fluid, cross-culturally and generationally meaningful. In this way, George Lucas is a bit like the Tolkien of sci-fi, the only difference being that, while most revere Tolkien for the way he revolutionized the fantasy genre, Lucas, most particularly since the 2000’s, has been derided for his work in the science fiction genre.

“I did research to try to distill everything down into motifs that would be universal. I attribute most of the success of to the psychological underpinning, which had been around for thousands of years and the people still react the same way to the stories as they always have,”

George Lucas

This is evident in the OT, but it’s there in the PT as well. The PT pulls more heavily from the archetypes of Greek tragedy, and the cultural practices and belief systems of the great eastern religions (which, if you like, you can read more about in Julien Fielding’s portion of Sex, Politics and Religion in Star Wars: An Anthology) as well as the original archetypal sources. This amalgamation of relatable material sources come together in the six film Saga to create a mythic compendium for humankind.

People are terribly fond of perpetuating this idea that Lucas let Star Wars get away from him, that he ruined his story by trying to write more, despite the fact that, by the time between the making of Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, he had already conceptualized what would become the basis for the prequel films.

In Greek drama, a work is considered to be seminal if it causes the audience to experience emotions on a wide range, vicariously, through the characters. In doing so, the ancient Greeks believed you could come to understand others, gain empathy, and learn to work through your own issues, as well as gain a greater understanding of the world as a whole. This concept is called catharsis, or a purifying or figurative cleansing of emotions. It is a purging of one’s emotional discord through the viewing of another’s tragedy. Greek drama was generally focused on dealing with current/relevant issues, frequently posed difficult political, social and cultural questions, and was intended to educate the audience. While the PT emulates this most specifically, the influence of Greek drama can be seen in the OT as well, in addition to its more more medieval and Western genre influences.

In A New Hope, Luke is the youth setting out on a journey. This concept is so ingrained in the hero archetype that you can find it in literally every piece of fiction ever written. (As a side note, it is also the basis for the Fool card in a typical Tarot deck). But ANH does not fulfill Luke’s journey — he is not a Jedi yet. In Empire Strikes Back, Luke reaches his peripeteia, or turning point, where he must confront Vader, but Vader, to his, and the viewer’s, extreme distress, is his father, the very figure of light and good who inspired Luke to want to be a Jedi in the first place. Even the infamous moment of revelation – “No. I am your father,” – has a name in the annals of Greek drama: anagnorisis, the moment of discovery. No longer is Luke’s heroic journey about becoming a Jedi, his journey is now something far more selfless. Only at the end of Return of the Jedi, do we discover what he’s really been working towards: the redemption of his father. But even so, with the OT alone, we still only have half of a Greek tragedy here.

There’s a theory out on the web called the Star Wars Ring Theory, that’s actually less of a theory, and more just a collection of purposeful moments in the saga that someone (Mike Klimo) realized were purposeful and put together in one place for people to look at and marvel over. It has its own website. I highly suggest checking it out, as it’s very well written and organized. I won’t spend much time on the particulars here. The general idea is that the films work through a technique called ring composition, and that the prequels are supposed to harmonize in a complementary way with the originals so that they rhyme together. This falls nicely in with the concept of the originals being the second act of a Greek drama, and the prequels being the first act. Most Greek drama is formatted like this:

(From the website of Bruce MacLennon at UT-Knoxville – please feel free to skim this, if you’re still reading by this point. You should get the picture quickly enough)

Typical Structure of a Tragedy

Prologue: A monologue or dialogue preceding the entry of the chorus, which presents the tragedy’s topic.

Parode (Entrance Ode): The entry chant of the chorus, often in an anapestic (short-short-long) marching rhythm (four feet per line). Generally, they remain on stage throughout the remainder of the play. Although they wear masks, their dancing is expressive, as conveyed by the hands, arms and body. Typically the parode and other choral odes involve the following parts, repeated in order several times:

Strophê (Turn): A stanza in which the chorus moves in one direction (toward the altar).

Antistrophê (Counter-Turn): The following stanza, in which it moves in the opposite direction. The antistrophe is in the same meter as the strophe.

Epode (After-Song): The epode is in a different, but related, meter to the strophe and antistrophe, and is chanted by the chorus standing still. The epode is often omitted, so there may be a series of strophe-antistrophe pairs without intervening epodes.

Episode: There are several episodes (typically 3-5) in which one or two actors interact with the chorus. They are, at least in part, sung or chanted. Speeches and dialogue are typically iambic hexameter: six iambs (short-long) per line, but rhythmic anapests are also common. In lyric passages the meters are treated flexibly. Each episode is terminated by a stasimon.

Stasimon (Stationary Song): A choral ode in which the chorus may comment on or react to the preceding episode.

Exode (Exit Ode): The exit song of the chorus after the last episode.

Typical Structure of a Comedy

Prologue: As in tragedies.

Parode (Entrance Ode): As in tragedies, but the chorus takes up a position either for or against the hero.

Agôn (Contest): Two speakers debate the issue (typically with eight feet per line), and the first speaker loses. Choral songs may occur towards the end.

Parabasis (Coming Forward): After the other characters have left the stage, the chorus members remove their masks and step out of character to address the audience.

First the chorus leader chants in anapests (eight per line) about some important, topical issue, typically ending with a breathless tongue twister. Next the chorus sings, and there are typically four parts to the choral performance:

Ode: Sung by one half of the chorus and addressed to a god.

Epirrhema (Afterword): A satyric or advisory chant (eight trochees [long-short] per line) on contemporary issues by the leader of that half-chorus.

Antode (Answering Ode): An answering song by the other half of the chorus in the same meter as the ode.

Antepirrhema (Answering Afterword): An answering chant by the leader of the second half-chorus, which leads back to the comedy.

Episode: As in tragedies, but primarily elaborating on the outcome of the agon.

Exode (Exit Song): As in tragedy, but with a mood of celebration and possibly with a riotous revel (cômos), joyous marriage, or both.

As you can see from reading the format of both the tragedy and the comedy, even the basic structure of Star Wars is owed to Greek drama. The prologue is akin to the famous ‘opening crawl’, the inclusion of “3-5 episodes”. The Agôn, from the comedy, a reminder of scenes early in ANH featuring Threepio and Artoo bickering. But even more intrinsic is the arc that Anakin Skywalker follows. As a young boy, Anakin’s whole purpose in life is to help others. He wants for others without wanting for himself. He has no concept of selfishness, because, as a slave, nothing belongs to him, except his mother. His mother, at least, is his. He has spent his whole life with nothing except her, and then, as he gains his freedom, he loses her. Fear of loss is Anakin’s hamartia, his tragic flaw. He is taken from his mother, the only thing ever truly his to have, and, as such, grips deathly tight to any small token he’s offered, terrified to lose it in the same way. Really, it would have been kinder to leave him on Tatooine.

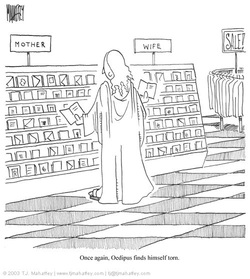

All Greek heroes have a tragic flaw, and Anakin is no different. Like Oedipus, we watch Anakin rise, beloved by others, put up on a pedestal, proclaimed the Hero With No Fear, when all Anakin can do is fear, not for himself but for others. His selfless desire to help others grows into a selfish desire to keep them safe, not so that they might not hurt, but so that he might be spared. Anakin is more human than any other character in Star Wars, almost uncomfortably relatable in the way that no one wants to admit. But being on the pedestal has its cost. He’s told over and over that he’s the Chosen One, just like all Greek heroes, and so, like all Greek heroes, Anakin develops hubris: pride and arrogance. He is told he is powerful and Chosen, but he is constantly put down because the Council itself doesn’t know what to do with him. He cannot help but develop pride in place of humility as a coping mechanism. What better way to be acknowledged than to become the best? Failure is antagonistic to the person Anakin believes he needs to be, the person others believe that he is. And Anakin falls into the trap easily, because not one person can see that it’s foundations have been laid by the flattery that Palpatine offers the young Anakin early on. He comes to believe he deserves it, comes to thrive off of it. Because without it, Anakin has nothing. The more tightly he grips, the more slips through his fingers, just like sand. And by the time that Anakin has his own epiphany, it’s too late. Like Oedipus, who gouges out his own eyes, Anakin resigns himself to the chains of bondage to his Master and to the Darkness; he leaves the literal bonds of slavery as a child, spends the Clone Wars fighting for ideological freedom, and only ends up exchanging one existence as a slave for another in the shell of Vader.

Anakin, regardless of the existence of midichlorians and anyone’s opinion of them, exists relative to the state of the galaxy. He is not Luke, he is not the youth of western literature on a journey; that is Luke’s role. Anakin’s role is that of the demi-god of Greek and Roman origin. When Anakin rises, the galaxy rises with him, when Anakin is in turmoil, the galaxy is in turmoil, when Anakin falls, so falls the galaxy. Anakin is intrinsic to the galaxy because Anakin, like so many other mythological demi-gods is an avatar for the gods or, in the case of Star Wars, the Force. Regardless of any one person’s views on the Force (which are extremely disparate and widely varied, so we won’t broach that subject here) this fact is indisputable. Anakin, as the Chosen One, who will “bring balance to the Force” is it’s avatar. When Anakin is claimed by the Dark, the Jedi Order’s zenith is reached, the Balance is tipped, and the Order descends into darkness with Anakin, just as his return also signals theirs.

The title Return of the Jedi doesn’t just reference Luke becoming a Jedi, but Anakin’s return to the light, and with it, the ability for the Jedi Order to once more flourish. In this he is much like Beowulf, when the Geatish hero sacrifices himself to defeat the dragon at the end of the epic poem. Failure would spell ultimate destruction for Beowulf’s people and country, just as, had Anakin failed to destroy the Emperor, the Jedi and the Galaxy would truly have been wiped out. Anakin himself has to die, however, because he is what tips the scales. Once he dies and becomes one with the Force, only then is balance restored. Balance, meaning not, as it is erroneously insinuated among so many, the return of the light, but rather the dominance of neither side. Everything evens out eventually. Just as in our world nature finds a way to balance the scales, so does the Force want naturally to be equal and proportionate in its darkness and its light. Without this, without Anakin’s intense ties to the state of the galaxy, Star Wars ceases to be a myth at all. It cannot support the format without an Achilles or a Jason or a Beowulf at the helm.

So where does The Force Awakens go wrong, all matter of opinion aside? Why did an OT fan, a general audience viewer, and a Saga fanatic alike all pan the touted ‘sequel film’? What things in the equation were changed? Why does Grandma’s cookie recipe suddenly taste store-bought? The Force Awakens overturns all the concepts previously explained, acting as if these long-established and intrinsic elements of the coherent myth are suddenly in need of subversion. It is anathema to the very prospect of it. While it fulfilled many fans generally acknowledged desired return to the OT, (in characters only, not in concept, which I’ll elaborate on) and allowed fans to glut themselves on nostalgia (to the point of near blatant plagiarism of ANH) it does not follow the formula set forth as precedent by all six preceding films, original trilogy and prequel trilogy alike. It completely lacks a hero archetype to carry the myth. None of the new characters have an arc that complies to these basic principles. To try and create a new ‘Chosen One’ from any of these characters would be utterly contrived. In addition to that fatal flaw, TFA physically denies the character arcs of all the original trilogy’s main cast, because the film spends too much time looking back, and not enough time looking forward.

Luke, as we determined earlier, is characterized by his journey to redeem his father. Even without taking the Prequels into account, this is factually the purpose of Luke’s journey. Luke exists to return his father to the light. His greatest accomplishment lies not in the destruction of the Death Star, but in the destruction of the hatred in his father’s heart. Luke – literally meaning light – is a paragon of goodness. His main characteristic is his stubborn refusal to give up on people. He believes fiercely in the goodness of others and learns over his journey that the galaxy – and indeed the world – do not exist in black and white, but shades of grey. He is the audience proxy. We share his happiness, his grief. We are on the journey with Luke.

When asked about Luke’s absence from the film, J.J. Abrams said the following:

“Early on I tried to write versions of the story where [Rey] is at home, her home is destroyed, and then she goes on the road and meets Luke. And then she goes and kicks the bad guy’s ass. It just never worked and I struggled with this. This was back in 2012. It just felt like every time Luke came in and entered the movie, he just took it over. Suddenly you didn’t care about your main character anymore because, ‘Oh fuck, Luke Skywalker’s here. I want to see what he’s going to do.’ “

This is exactly his problem. In relegating Luke’s character to being in absentia for almost the entirety of the film, Abrams likewise decided to disregard everything previously determined about the character. He altered the very facts that defined Luke Skywalker, and his journey. This action is commonly called character assassination. Luke, who stubbornly refuses to give up on anyone, even Darth Vader, is now a man who leaves everything and everyone he knows and goes into exile, leaving his nephew to drown amidst the tides of the Dark Side. Abrams has tried to turn Luke Skywalker into a myth, but he’s missed the point. Luke cannot be ‘a myth’ if his character arc, as now retconned by Abrams, ends in meaningless failure. The whole point of a myth is to remind people of a basic and universal truth: myths exist where good eventually triumphs over evil, where there is some purposeful resolution. In failing to understand that, Abrams has undermined the entire purpose of the six film Saga as a whole. My feelings about the plot aside, this is in direct opposition to everything anyone familiar with the OT knows about Luke. His absence alone is out of character to what has previously been established, and is thus a mark against the film. Perhaps, when Mr. Abrams had so much trouble trying to write his early drafts of The Force Awakens, and couldn’t manage it with Luke in the story, he ought to have taken the hint. This barely scratches the surface.

Star Wars, as it was, either Episodes I- VI, or IV-III, depending on how you want to look at it, is a complete entity. Other stories could and did exist in T-canon and C-canon, but they were all secondary to the Saga itself–aka, the six films that told the story of Anakin Skywalker’s rise, fall and redemption. By attempting to continue an already completed story, Abrams found himself suddenly between a rock and a hard place. The simple fact of the matter is that no sequels, no matter who might have written them, ought to have existed as ‘canonical’ films in addition to the Complete Saga.

The Force Awakens falls flat because it is not part of the Skywalker Saga, even though it claims to be. Indeed, this very claim seals its ultimate failure. It does not follow the conventions, it has no place in the story, it cannot carry on its main themes, because said themes are already concluded. In the PT and the OT, Lucas wrote exactly the story he’d intended. He didn’t write the story people wanted, didn’t allow peer pressure, and fan pressure, to alter his course. Everyone fantasizes about Elizabeth’s life with Mr. Darcy after they get engaged at the end of Pride and Prejudice. They might even read a book about it, and, if it’s terrible, they can say ‘oh, it’s just a book. Jane Austen didn’t write it, I can just forget about it, and move on with my life’. But no one wants to watch a movie about it. Sure, you’ll read fanfiction about Nolan’s Bruce Wayne, kicking it in Europe with Selina Kyle, but no one wants a movie about it. It won’t fit the paragon, wouldn’t accent the story, because it has no place in a story centered around myth and the heroic archetype. The prophecy has already been fulfilled. The fallen hero, redeemed by his son, gives himself to save his son and the galaxy. The natural end of any story falls at this point. The Skywalkers’ story ends with a balancing of the universe in which it exists. To go any farther, and to claim to be a true, necessary part of that story, is to deny the purpose for which Star Wars was written. To move forward from this point, and try to maintain that it’s still part of the Saga, is a completely erroneous act.

Therein lies the fault of The Force Awakens. Warmed by scenarios pulled too liberally from ANH, pressured into disliking the prequels due to popular bias, lulled by the familiar faces of Han and Leia despite their blatantly regressed characterization, fans have been coerced into ignoring the wrongness of the characterization, the language, even the cinematographic style of TFA. It does not fit into the cohesiveness of the Skywalker Saga because it cannot be part of the Saga. The Saga is over, complete. It is a vision fulfilled.

Rogue One, on the other hand, does not fall victim to this. It does not claim to be a part of the Saga. It exists without intentionally altering facts crucial to the plot of the myth. It exists as a supportive side note only. The writers of R1 did not fall victim to the same hubris that haunts Abrams and Disney. R1 knows exactly what it is. It’s C-canon. Continuity to be utilized or ignored at whim, or as needed. It’s a Star Wars Story, not Star Wars itself.

Yet, even that C-canon has been desecrated, as to let it stand would threaten the viability of Disney’s new venture. The Force Awakens is nothing more than a fanfiction that someone decided would be their ‘new canon’, retconning things that have been considered broadly ‘continuity canon’ for nearly forty years. Even books like Alan Dean Foster’s Splinter of the Mind’s Eye, which was the first novel to be written in the Star Wars universe after A New Hope was released, have been discarded. Authors, such as lauded Star Wars veteran, James Luceno, have had their works invalidated as well. When writing the new EU canon novel, Tarkin, he said:

“I chose not to really reference too much EU material only because of the setting of the story, but it was still there. It was still there to pick and choose from. I think going forward what may happen is you may see writers writing around some of that older material that’s now classified as Legends – writing around it rather than trying to overwrite it.”

Why is this? Simply because there was no reason for it to be overwritten at all. In order to accommodate the ‘new canon’, old canon had to go. All of it. Even things from the Old Republic, dating back years prior to the prequel trilogy. Even the film novelizations. Why is this? Because the sanctity of the intellectual property that was George Lucas’ Star Wars has become the new money monster behind the Disney Machine, Darth Mickey cracking the whip behind it’s chariot.

While The Force Awakens has its merits, they are few indeed, and the only one that deserves listing is the diverse casting. We live in a culture of reboots, remakes, and revivals. Sequels and ever-growing franchises are the lifeblood of Hollywood and major production companies. Most films are based on books. Original material is almost non-existent. This is exactly the world that George Lucas was trying to undermine when he joined American Zoetrope and later when he opened Lucasfilm. Instead, he created a new and just as intellectually stagnant Hollywood, where we laugh at the same jokes in every Marvel film, and call them spectacular, or watch each director’s new vision of Batman, adding to the ranks of the tens of Batman franchises that have existed in film and television going all the way back to the sixties. Where, just like Tolkien, new science fiction hasn’t been released. Instead, it just tries to be Star Wars, Dune, 2001: A Space Odyssey or any other seminal work of fiction. Pale reflections of the greatness that inspired them. Hollywood, and the audience it panders to, eat these up readily.

In 2012, in effort to keep Lucasfilm employees from being laid off, George Lucas sold his company, and along with it, his magnum opus, to Disney for $4.5 billion, giving much of the money to charity. All the same, much of the LucasArts branch staff was let go in 2013, as Disney continued to merchandise, once more acquiring the rights to all Star Wars comics, which had been sold by Marvel (also now a Disney subsidiary) to Darkhorse many years prior.

The prevailing issue behind TFA’s success, the reason that Disney has, for now, gotten away with its blatant use of Star Wars to front commercialism while it nurses its growing monopoly, is that the myth archetype is no longer preferred among the public. Consistently, in television and film, the mythic arcs are panned. People prefer the ‘monster of the week’ episodes of The X-Files and Supernatural to the arguably more impactful myth arcs–that is, of course, disregarding the relative quality of the arc, which varies considerably.

Now, television is a different animal than film, but this still applies to the reception and perception of Star Wars. Its myth arc is continually disregarded to the point of being forgotten. I was speaking with a colleague of mine, a fellow English teacher, who had never seen the prequels out of distaste based on hearsay, and she grew confused when I mentioned Vader’s redemption at the end of Return of the Jedi. She’d forgotten all about the culminating moment of the entire Saga. His redemption is the climactic moment of the film. He rose up, and destroyed the Emperor, returning to the light out of love for his son, who, despite everything, continued to believe that there was good in him, even when Anakin did not believe it himself. When I asked that colleague just what she thought Star Wars was about, she couldn’t give me an answer.

This illustrates something fundamentally wrong with the way Star Wars is perceived as a film series, as if it is but a series of shallowly conceived, explosive summer blockbusters. If that was what fans had been looking for, walking into the prequels, even walking into the originals, I can’t help but understand their confusion when they were required to face the hard political questions posed by the prequels, or the chilling moral questions of the originals. Science fiction has this unfortunate stigma attached to it that says it can’t be taken seriously, yet serious science fiction authors do exist. Ray Bradbury was a science fiction writer, who wrote ideologically and culturally challenging literature that revolutionized the genre. Stories like Fahrenheit 451 that are rightfully lauded for their foresight and eternally relevant social commentary. However, like Clotworthy says in Empire of Dreams, Star Wars, despite being billed as such, is not actually science fiction so much as science fantasy. George Lucas is a visionary, who saw that traditional mythological archetypes from the world over had a unique ability to connect with all people, regardless of age or gender or origin. Commonly, Star Wars is called a space opera, which jives with the idea of Star Wars as a Greek drama. Operas aren’t set it the present, they aren’t common, they speak to the mind of the people, but offer them something beyond what they normally partake in. Star Wars, at it’s heart, is actually a fantasy, a fable, an opera, of a long ago past, something that is set in stone, that cannot be altered, because it already happened. Star Wars is the new Beowulf, is the new King Arthur, and like those stories, stands as testament to the concepts which are therein contained. Someday, long after we’re gone, a new Homer will tell the Skywalker Saga around a campfire.

Releasing Star Wars under the flagship of the science fiction genre allowed Lucas’ fantasy mythos to be a vessel for that message to people who would never have otherwise given such a story a second glance. Star Wars is the story you SparkNotes’ed in high school. Star Wars is the story you started reading but the archaic language bored you, so you gave it up. Star Wars is the story you thought was cheesy, stupid, outdated, irrelevant, unimportant, not relatable. Star Wars is far more than one of the greatest science fiction franchise’s ever made.

The sheer amount of effort and dedication that George Lucas put into the creation of a viable modern myth is astounding. It is the painstaking incorporation of these elements that has allowed Star Wars to become the cultural phenomenon that it is. Without the literary and mythic scope of the story, Star Wars would be just another forgotten footnote in the annals of science fiction film history. It would be a one film endeavour that could never have had the cultural and social repercussions that make it stand out today. The Saga stands inimitable, an epic myth for the modern age, and any attempt to recreate or expand upon it reveals those attempts for the sham, the empty, meaningless husk that it is: a soulless, commercially driven, pathetic attempt at recapturing one man’s genius of vision. Any undertaking to add to the Saga that does not participate at the same level of mythopoesis as laid forth by the original, that does not fall in line with the priorly determined mythic canon that came before, will inevitably be inimical to its own purpose. Unless the proposed concept falls within those predetermined parameters, any subsequent additions will inevitably fail, regardless. As George Lucas once put it in the commentary of the documentary Star Wars to Jedi, “Special effects without a story is a pretty boring thing,”, and Star Wars without mythopoesis, is just simply not Star Wars at all.

Resources:

https://www.scifinow.co.uk/news/star-wars-7-exclusive-james-luceno-on-tarkin-eu-canon/

http://www.starwarsringtheory.com/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k9mgX4r-bbE&t=716s

https://web.eecs.utk.edu/~mclennan/Classes/US210/Greek-play.html

Quote of the Day

“How often when we are comfortable, we begin to long for something new! ”

― Jakob Grimm